The Uncertain Case for Equal Weighting Amid Market Concentration

Equal weighting has outperformed the market, but will that persist?

Amid soaring valuations among the so-called “Magnificent Seven,” investors have increasingly looked to equal weighting as a remedy for over-concentration in the S&P 500. Over the past 27 years, equal-weighted products have, on average, outperformed their market-cap counterparts – a provocative signal for those questioning the merits of traditional index funds.

This article examines whether a shift in weighting strategy might redefine the landscape of passive investing.

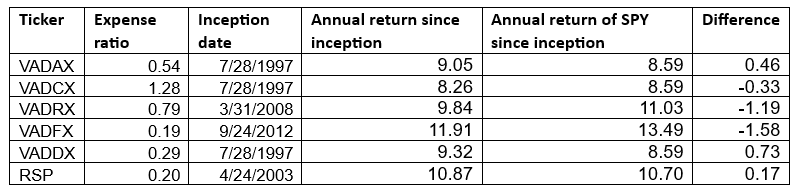

The first equal-weighted product, the mutual fund VADAX (then one of three share classes), began trading on July 28, 1997. It was followed by the ETF RSP, with an inception date of April 24, 2003. Across all share classes, the AUM of equal-weight S&P 500 products is now just over $79 billion, 92% of it in RSP.

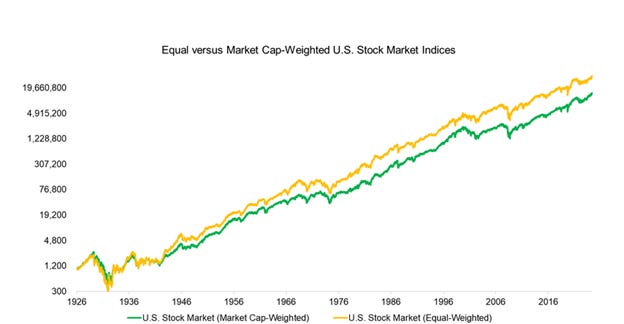

Before looking at the performance of these products, let’s see how an equal-weight index performed against an S&P 500 index. Nicolas Rabener, who runs the excellent web site Finominal, constructed an equal-weight index using the CRSP database, going back 100 years:

The equal-weight index outperformed the market by 100 basis points annually, although it had a slightly higher volatility (17.6 versus 17.1 standard deviation).

But what worked in theory did not work as well in practice. Here is the since-inception performance of each of the equal-weight products versus an S&P 500 index ETF (SPY):

Data provided by Morningstar Direct except for SPY returns. SPY returns provided by this site. The first five securities are different share classes of the same open-end mutual fund. The last is an ETF. All products are offered by Invesco. Data as of 3/21/25.

The average standard deviation of those products was 19.77 versus 18.93 for the S&P 500 total-return index.

The immediate takeaway is that none of these products have matched the 100 basis-point advantage of the equal-weight index over the market. That’s to be expected, given the expense ratios of these products. But It’s very tempting to allocate to a product like VADDX that has outperformed the market by 73 basis points over nearly 28 years with just slightly higher volatility.

But there are several mitigating factors to consider when viewing these results.

I used SPY as the proxy for the S&P 500. It has an expense ratio of approximately 9.5 basis points. The Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO) does not have as long a historical record as SPY, which is why I did not use it in this analysis, but it has an expense ratio of 3 basis points. That difference of 6.5 basis points would wipe out a third of the advantage of RSP over SPY.

Moreover, SPY had an expense ratio of 20 basis points at inception, whereas the expense ratio of RSP has always been 20 basis points. If one were to retroactively adjust SPY and show hypothetical returns based on its current expense ratio (or were to use the expense ratio of VOO of 3 basis points), the remaining advantage of RSP over SPY might disappear.

Equal weighting means overweighting the smaller stocks in the S&P 500 and underweighting the larger ones. But don’t rely of the supposed “small-cap advantage” as justification for the outperformance of equal weighting. Thanks to the work of Gary Miller and Scott MacKillop, which was later confirmed by Michael Edesess, we have known for nearly 15 years that small-cap stocks have not outperformed the market on a risk-adjusted basis. The small-cap advantage has not existed since Rolf Banz first identified it in 1981, and he was wrong to claim that it existed before he published his results.

An equal-weight index product will not “clear” the market. As the demand for these products increases, the prices of the smaller, less liquid stocks in the index will rise. Equal-weight products already have considerably higher transaction fees versus the market (RSP has a turnover of 21% versus 3% for SPY). Those transaction fees, which are not reflected in the expense ratio, will grow disproportionately with asset flows.

This is not a problem now, with $79 billion out of $32 trillion in assets in U.S. stocks. But if it were to become a problem, it is likely that it would go unnoticed, since asset-flow-induced changes to valuations are difficult to detect.

Equal weighting should be pursued over long time horizons. Rabener’s work showed that in six of the 10 decades he studied, market-weighting outperformed equal weighting, or the difference between the two was approximately zero. The outperformance of equal weighting was concentrated in three decades – 1933-1943, 1974-1984, and 1994-2004.

The outperformance of VADAX and VADDX relative to RSP is not due to their open-end mutual fund structure versus the ETF. RSP should perform better because it has lower expenses. The difference is because the period 1997-2003 (before RSP was introduced) favored equal weighting more than the time since 2003.

Equal weighting represents an active deviation from traditional market-cap indices, offering a robust historical performance for those with long-term horizons and a tolerance for greater volatility. While the century-long outperformance of equal-weight strategies remains a compelling anomaly, investors should remain circumspect.

There is no guarantee that the anomaly will persist. Typically, that is not the case.

Robert Huebscher was the founder of Advisor Perspectives and its CEO until the company was acquired by VettaFi in 2022. He was a vice chairman of VettaFi/TMX until April 2024.

Thank you for that helpful bit of information.

Andy, why is it easier to model EW than MW? Seems like it should be easy to model either one.